In 2002, Andrea Heller creates Netze, a work composed

of two large sheets of paper (250 x 150 cm each) upon

which she draws, in ink, the motif of a diamond grid

from which she then cuts out all the voids between the

intersecting lines. The work is fixed to the wall at the

top and unfurls to the ground. It communicates the

general impression of an aviary, a fishing net or even

wire mesh, with the difference that the cut paper

is extremely fragile. The title Netze also embodies the

other sense of the word, networks, be these human

or from the world of IT.

This work could be considered as fundamental to

her oeuvre. She introduces a technique, ink on

paper, and a motif, the diamond grid, which become

recurrent. She opens up fields such as architecture

(the wire mesh) and nature (the aviary and the fishing

net). She plays with contrasting sensations, the

fragility of the cut paper and the solidity of the net or

the mesh. And, while on the subject of contrasts,

there is a photo (1) of a young man on all fours over whose

body Netze is draped. This records a private action

realised by the artist and underlines the ambivalent

nature of the work which, although fragile, can

still immobilise a human body. The artist invites us to

reflect upon such notions as vulnerability, entrapment,

protection and domination, to which the body, be

it human or animal, is often subject.

The motif

Andrea Heller regularly employs the chequerboard

motif, adapting it in a free and organic manner. Between

2007 and 2012, three works on paper entitled Versteck

develop the motif in a way that is both supple and rigid.

They evoke a blanket with a geometric print that is

draped over forms which, as hypothetically underlined

by the title, could be bodies. One can also sense

a mineral quality, like a gypsum flower with a regular

form and delicate edges. Or a reference to buildings

designed using 3D software that enables façades

to be sculpted like rippling sails. Other works suggest

a more natural development of the diamond, lending

it an oval form: Widerstand, 2011, is composed of two

clusters or groups that come together, drops above

and domes below. Are these forms vegetable, mineral

or cellular? Or is this a clash between two crowds

from above? Such questions frequently occur when

looking at the work of Andrea Heller. One imagines that

one sees something familiar but, when the scale or

viewpoint shifts, the reference changes completely.

Schneegrenze I, II and III, 2011– 2013, refer more clearly

to rounded mountain peaks while Untitled (smoke),

2015, schematically portrays the eruption of a volcano.

The artist is fascinated by landscape, meteorology,

the slow rhythm of geology and the more urgent rhythm

of the seasons.

Andrea Heller never stops fine-tuning this motif:

the initial mesh becomes the diamond grid, the

diamond evolves into a triangle or a pyramid, is rounded

into a cone or a dome, which, depending upon its

position, could evoke a bowl, a mountain, a thimble, a

breast or a volcano. A game of solid and void, which

is played with geometrical rules, but which is also

vegetable and mineral, or even sexual, as in the case of

the elongated cones that are alternately full and empty.

The archive

How does Andrea Heller assemble her formal vocabulary

and her thematic explorations? In order to

understand this it is useful to dip into her archive, which

she started in 1998. This is composed of photos

taken by the artist and images cut from newspapers,

found on the Internet and even scanned in books

and other publications. When free newspapers first

appear around 2002, she is struck by the proximity

of very different sorts of images, of war, natural catastrophes,

glamour, politics, sport and oddities. She

cuts many out and removes them from their contexts

in order to write her own story. Between 2005 and

2006, she creates collages of images taken from her

archive (2). In 2015, she goes much further in a similar

direction in Vitrine 1, 2 and 3. Here, she creates covers

in the shape of irregular domes that she makes by

gluing together pieces of glass. These covers then

lend their form to plinths upon which series of images

are assembled. The subjects, such as landscapes,

animals, plants, catastrophes and buildings, often

appear as fragments and make great use of the odd

(a sheep buried under its own wool, shapes hidden

under tarpaulins, mysterious rituals, UFOs) or the impermanent

(burned-down houses and forests, a

village destroyed by an avalanche, a caravan cut in half

by a tree). This archive irrigates all her work in a way

that is more or less direct and recognisable.

Reference documents

The form of the glass covers to the vitrines refers to

the contents of such hippy literature from the 1970s as

Shelter or Nomadic Furniture (3), which contain oper-

ating instructions for the construction of temporary

self-made buildings. These publications from the ‘Do

it yourself’ (DIY) culture are a mine of information

about caves, huts, tents and domes and about their

history and special features amongst both Amerindians

and Europeans. They explain the construction of each

type of dome, the structure of which is based on the

famous form of the triangular/diamond grid as used by

Andrea Heller. They address such questions as

materials and nomadic ways of life, tell us about energy,

water, food and waste and put them in their rightful

place at the dawn of the ecological movement.

Several years later, around 1980, Andrea Heller’s

parents join up with other families to develop a

cooperative housing project. Interested in better understanding

the context that had fostered this way

of life, the artist recently discovered a work devoted to

the Selbstbau (self-building) movement, Das andere

Neue Wohnen – Neue Wohn(bau)formen (4), whose observations

on amateur building in Switzerland largely

draw on an initiative of the Federal Council, which is

described as follows: ‘In 1978, the Federal Housing

Office, a young body run by active officials, and which

was also one of Berne’s most significant developers,

organised a working congress devoted to “homes built

and administered by their inhabitants”.’ This movement

is a sort of ‘Swiss riposte’ to American DIY culture.

Architecture

The many works that express her interest in architecture

include Überbau, 2005, which portrays a heap

of red wooden cubes. This ink drawing on paper evokes

a stylised medieval castle, a breakwater or a setting

designed to welcome actors and their actions. Andrea

Heller chooses to use the German title because

this permits her to play with the double meaning suggested

by the terms ‘theoretischer Überbau’, which

describes the theoretical structures conveyed by a work

of art, and ‘Überbauung’, which in Switzerland refers

to buildings realised on former agricultural or industrial

land in accordance with land use planning. The references

to self-building are not far away.

Panzersperren, 2006, explores the milieu of defensive

architecture because, in Switzerland, these truncated

pyramidal forms are associated with the ‘toblerones’,

the concrete blocks that were arranged at the start

of the Second World War as dragon’s teeth: lines of fortification

against the German menace that can still

be found today (5). Barricade, 2015, confirms this attraction

to protective structures by revisiting both the medieval

castle and the provisional barriers created during

street protests.

Andrea Heller has designed her first monumental

installation, L’Endroit de l’envers, 2019, for the Salle

Poma in Kunsthaus Pasquart. Supporting each other,

the panels recall a house of cards, which aspires to be

a great work yet has the delicate balance inherent to this

ephemeral construction game. With their irregular

dimensions and sombre-coloured surfaces the panels

produce a wide range of impressions depending

upon the perspective of the viewer and, for the first time,

are not an image on paper or canvas but a sculpture /

structure / architectural element that establishes

its presence spatially and is discovered as one moves

around it. This work is, simultaneously, a sort of architectural

fragment from DIY culture, barricades built

by street fighters and a children’s game on an adult

scale. As an ensemble it is ambivalent: between micro

and macro, resistance and fragility, constructive and

destructive, playful and political.

Nature

Nature is another of Andrea Heller’s preoccupations.

In the series Meteorit, 2005 – 2006, large surfaces,

blackened with ink and spray paint and bearing an

organic variant of the triangle / diamond motif, attest

to an interest in the long timescales of the minerals

that form the planets. One can almost ‘feel’ the materiality

of the stone due to the deep and intense treatment

of the colour and the motif. Fundament, 2014, a

work in watercolour and ink on paper, presents another

black surface, this time suggesting the interior of a

cave with thick stalagmites and delicate stalactites in

a mysterious and obscure atmosphere. The sculptural

work Untitled (pompons), 2007 – present, has a

special status, because it is both site-specific and

evolving. Composed of pompons made from black

wool, it is different every time it is presented because,

firstly, it may be placed in front of a window or fixed

to a radiator or a pipe on the ceiling and, secondly, it is

constantly growing as the artist adds more pompons.

As a result, the pompons take on a meaning very

different to that of a comforting ball of wool. Even if their

appearance recalls coral or volcanic rock, their proliferation

is more suggestive of mushrooms, spreading

viral cells or a colony of tiny living beings who bunch

together in hordes around, for example, a source of heat.

Hybridity

If the motifs of the diamond / triangular chequerboard,

the archive, architecture and nature highlight the

system of thought and practice of Andrea Heller, the

idea that encompasses her work as a whole is hybridity.

The framed three-dimensional ink and cut

paper work entitled Die Wurzeln sind die Bäume der

Kartoffeln (6), 2005, is symbolic of this. What does one

see? A priori, black trees with thick, pointed branches

and, at their feet, two inclined egg-shaped forms (7). The

title signifies ‘The roots are the trees of the potatoes’.

So, is this about trees or roots? The branches seem so

sharp: Is one in the world of plants or is this a scaledup

version of the blades of Edward Scissorhands? Do

the egg-like forms represent potatoes, ghosts or

hooded bodies? One can also see them as a nod in the

direction of the figures of the bear and the rat in the

film Der Rechte Weg by Fischli & Weiss.

The human body is one of the most hybrid elements

in the artist’s vocabulary. Reviewing her works one

sees, for example, heads and torsos in the form of carrots,

stalagmites, tubers, intestines, little towers,

menhirs, insects, coffins, balloons and rocks, usually

equipped with legs, sometimes with arms, which

form an anthropomorphic and phantasmagorical ‘bestiary’.

The body is also treated fragmentarily, as a

skull-potato-owl-penguin, a hand-glove-stele-wall or

even breasts-implants-bra-tea cosies-cheese dishespetit-

fours.

Three recent series take this hybridity even further.

On the one hand, four large ink drawings on canvas

bear the same subtitle (a specific place), a notion that

only exists in the head of the artist but becomes a

‘place’ on the canvas. Two rooms is a troubling fusion

of mountains and a face, Wall explores a condition

between the molecular and the built, No entry is located

at the interface between the mountain, the canyon

and minimal architecture while, in Shadows, a menacing

post-human silhouette appears to emerge from a

couple with building-like heads.

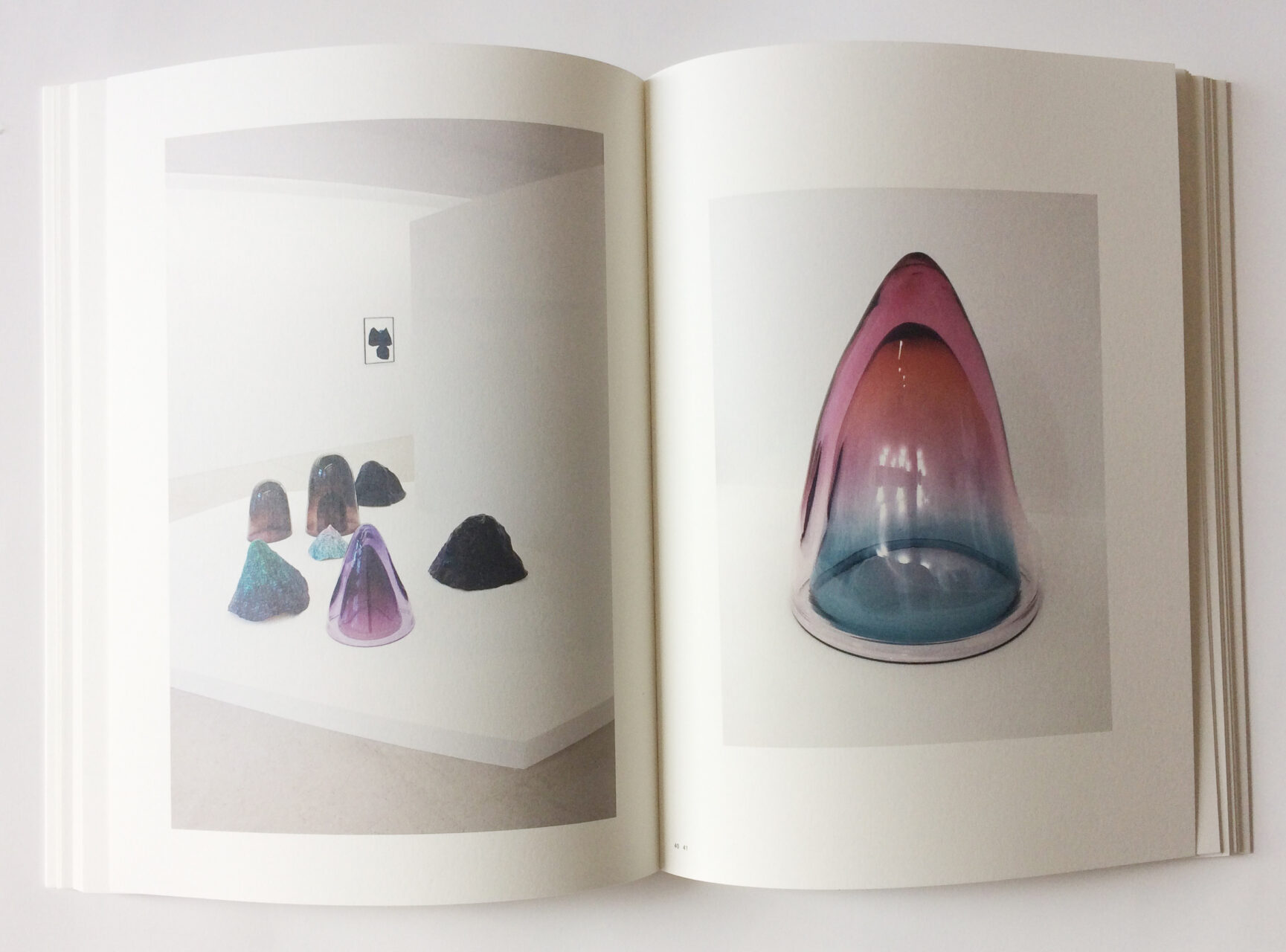

On the other hand, the series of sculptures Magnitudes,

2018 – 2019, explores the form of the cone,

more or less broad or long, opaque and with an irregular

surface for those realised in painted ceramic and

transparent and smooth for those in blown glass. The

references to the breast, the bowl, the vase, the

womb, the penis, the mountain and the volcano emerge

one after the other.

Finally, the series of plaster sculptures Terrain vague (8),

2019, which currently contains 37 elements, is composed

of casts that could constitute the beginnings of

an encyclopaedia of forms. One suspects that one can

recognise a Lebanese pitta bread, eggs in a wicker

basket, the bubble houses of the architect Antti Lovag,

an octopus, ancient cobbles, an archaeological dig,

a fortification by Vauban, an intestine, a pyramid or the

udders of a sow.

When one immerses oneself in the compositions of

Andrea Heller, one discovers, in addition to their

initial beauty, a depth, a visual intensity and, also, a conscious

sensitivity to the world. Her attraction to meteorites,

volcanos, caves and mountains testifies to

her close attention to life on earth. Her architectural

experiments illustrate her interest in human actions

vis-à-vis space, nature, meteorology and society. Her

relationship with the human body affirms a fantasy

that hovers between joy and gravity. By constantly

playing with scales and references, her oeuvre never

stops challenging the definitions and diagrams of our

certainties.

1) This undated photo appears on page 59 of the monograph Die

Wurzeln sind die Bäume der Kartoffeln, Zurich: Édition Patrick Frey,

2012.

2) Die beruhigende Aura der Tiere, 2005; Die Wut ist heftiger als der Ärger

und schwerer zu beherrschen als der Zorn, 2006; Hier auf dem Mond

ist es auch nicht viel besser, 2006.

3) Kahn, Lloyd (ed.), Shelter, Bolinas, California: Shelter Publications,

1973; Nomadic Furniture 1 and 2, New York: Pantheon Books,

A division of Random House, 1973 and 1974.

4) Das andere Neue Wohnen – Neue Wohn(bau)formen,

12.11.1986 – 4.1.1987, Museum für Gestaltung Zürich.

5) More than 2,700 ‘dragon’s teeth’, concrete blocks weighing nine

tons, were built as anti-tank obstacles between 1937 and 1941,

particularly at the foot of the Jura in the Canton of Vaud. Their

triangular form recalls Toblerone chocolate, to which they owe

their name.

6) This is also the title of the book published by Édition Patrick Frey,

2012, on the occasion of Andrea Heller’s solo exhibition at the

Helmhaus in Zurich, 2.12.2011– 29.1.2012.

7) The work is realised in Indian ink on cut paper, recto verso, and

the sheet is fixed between two panes of glass held in place by a

wooden frame. It was produced as a series of ten, each slightly

different.

8) The dimensions of these sculptures vary between 10 and 50 cm in

diameter.